|

|

|

A Soldier’s Life in the American Civil War

Joining up Nobody knows why ordinary men – the vast majority of them farmers – signed up. Writing in the 1940s & 50s, historian Bell Wiley suggested that they were not fighting for a particular ideology – particularly not for love or hatred of slavery. Instead, they joined because their friends and community were signing up, for adventure, to meet some requirement of masculine identity … or because they hated the enemy. In the South, women would send their petticoats to men who hadn’t joined up – in all perhaps 80% of Confederate males joined up. In the North, signing-up bounties and a wage of $13 a month attracted the poor and the destitute. Later in the war, of course, both sides conscripted soldiers. That said, after studying 25,000 letters and 250 private diaries, Professor James McPherson (1997) concluded that, especially in 1861-2, soldiers on both sides were motivated by ideology and patriotism.

|

Going DeeperThe following links will help you widen your knowledge: Basic account in Prof. Gallagher's Great Courses book

- Ch 7 on Soldiers (pdf) Virtul reality experience - includes videos showing defence and attack |

|

Discipline Most of the civilians who joined up were unused to any form of discipline, and found army life – with its ‘hurry up and wait’ culture – irksome. While small infringements might be given extra duties, a common punishment was ‘bucking (tying the man, for instance, to a field gun) and gagging’. Deserters were shot. Before the civil war, the federal army had comprised barely 15,000 men. That meant that almost all the rank-and-file, and most of the officers, in the Civil War, were ‘green’ and unused to battle. In the early battles of the war, generals on neither side could rely on their men to do as commanded. Union Private Theodore Gerrish described his first march as: “most ludicrous … an untrained drum corps furnished us with music; each musician kept different time, and each man in the regiment took a different step…. We marched, ran, walked, galloped, and stood still”. Marching quickly to Pittsburg Landing (1862) to try to take the Union Army there by surprise, Confederate troops sang, shot at deer, and practised their ‘rebel yell’ … and were still four miles short of the enemy by nightfall. Meanwhile, the readiness of the Union troops can be gauged by the fact that they were, nevertheless, taken by surprise when the Confederates attacked next morning.

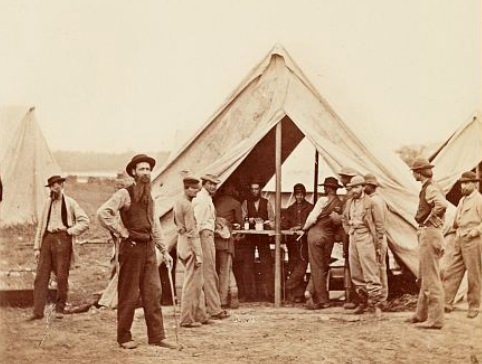

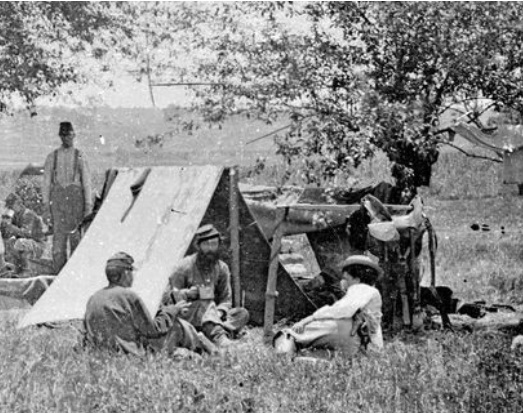

Life in Camp Very little time was spent fighting. The staple experience of a soldier’s life was the crushing boredom of camp. There were long hours of drill, cleaning and polishing uniform and weapons, ‘fatigues’ such digging latrines and collecting firewood, grooming horses and guard duty. Men filled the rest of their time with activities such as card games, chess and singing. The game of baseball first become popular among Union troops during the war. Many loved to receive letters, reading them over and over; those who could, wrote back – Confederate soldiers, lacking paper, wrote on anything they could get hold of, including the back of Union propaganda leaflets; when they had filled the paper writing left-to-right, they would turn it on its side and over-write bottom-to-top. Many soldiers attended religious worship, though proper young men were shocked by the language and debauchery of some of their comrades. Some of the female ‘camp followers’ were the upright wives of officers; others were prostitutes. Unknown numbers of women pretended to be men and joined up; of those who were found out, many were discovered when they became pregnant.

Food The full Union marching ration consisted in theory of 1lb of ‘hardtack’ and ¾lb of salted meat, along with coffee, sugar and salt, bulked out with desiccated (dried) vegetables. However, unreliable supply lines – especially where there were no railways – meant that even Union soldiers regularly went short. When this happened, Union troops were usually followed by a sutler (who sold provisions from a tent or the back of a wagon). Confederate troops, who were far less well provisioned, routinely relied for food on parcels from family and assistance societies, or were reduced to cornbread so full of husks that it tore the inside of their mouths; failing even that, it became a matter of ‘long forage’ – gathering wildflowers and stealing what they could from the local population.

|

|

|

Equipment Shelter was inadequate – Union soldiers were given ‘dog tents’ – two sheets of tent-cloth buttoned in the middle, which could be stretched between two bayoneted rifles. Confederate troops did not even have that. Pitched for longer periods in ‘winter quarters, some troops managed to build log barracks, to which they gave names such as: ‘Wiltshire Hotel’. Union troops were generally far better provisioned than the Confederates, who were generally left to look after themselves. By the end of the war, one soldier in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia noted that most of their supplies were articles captured from the Yankees, including their pants, underclothing and overcoats. Particularly valued were the Union rubber blankets, which they used as groundsheets.

Disease Theodore Gerrish noted: “the terrible sickness of the soldiers”, as typhoid, malaria, pneumonia, tuberculosis, scarlet fever and what we regard as mild children’s illnesses – measles, mumps and whooping cough – killed men who had no inbuilt immunity, knew nothing of germs or even basic sanitation, and were malnourished, cold and infested with lice and fleas. Dysentery killed more men than enemy bullets. Medical care was more terrifying than the wounds, which could go untreated for days, not hours, in a big battle – it took over a week to remove the wounded from the battlefield at Second Manassas, 1862. Wounds to the torso were untreatable and, even if you survived shock from the amputation of a wounded arm or leg, you were likely to die from sepsis in a world which did not use antiseptics.

Trench warfare The replacement of the smooth bore musket (barely accurate at 100 yards) by the rifle musket (accurate at up to 1 km) transferred the advantage of warfare from the attackers to the defenders, who dug themselves trenches and could inflict huge losses on any frontal attack. Many of the horrors we associate with the First World War were the experience of soldiers in the American Civil War. This led to some surprising reactions. Military archaeologists exploring battle sites often unearth unfired muskets, some of which had been loaded multiple times. There are reports of troops firing wildly over the enemy’s heads. This may have been the result of young, green soldiers panicking, but there is a theory that significant numbers of soldiers did so on purpose because, when it came to it, they could not bring themselves to kill another human being. Another interesting feature was the occurrence of homesickness (officially called ‘nostalgia’) – the Union recorded 5,213 cases, resulting in 58 deaths. One such, for example, was Frederic D. Whipple, a volunteer from Vermont who, sent to the infirmary because he was behaving strangely, “refusing to be nursed, after a few days he died, moaning … all the time, ‘I want to go home, I want to go home’.” In the mid-19th century, neither ‘homesickness’ nor ‘nostalgia’ meant the mild wistfulness we understand today; it is clear from the case of Frederic Whipple, that these men were suffering what we today would call shell-shock, or PTSD.

Desertion Being a soldier involved months away from home. And while Union soldiers signed up for a set period and received furloughs, Confederate soldiers signed up indefinitely and were routinely refused leave. Back home, crops went un-harvested and farms fell into decay. Meanwhile, the tiny pay that soldiers– especially the Confederate soldiers – received was insufficient to maintain their families, who were literally starving to death. There are hundreds of letters from Confederate soldiers’ wives begging them to desert and come home. Official figures show approx.. 103,000 Confederate soldiers (13-15% ) and more than 200,000 Union soldiers deserted, with some estimates as high as 280,000 (10-13%). Given the penalty for doing so, you should be able to gather what life as a Civil War soldier was like.

|

|

|

| |