|

|

|

BackgroundIn 1964, the Soviet Presidium dismissed Khrushchev, and in his place a team of three dominated the Soviet government – Leonid Brezhnev (Foreign Minister), Alexei Kosygin (Premier) and Yuri Andropov (Head of the KGB – the Soviet Secret Police). As in 1953 with Stalin’s death, the replacement of Khrushchev in 1964 led to instability in the Soviet bloc in eastern Europe, particularly as the Communist leaders tried to claw back the freedoms people had got used to:

In 1968, therefore, the USSR was “a weak hegemon: its leadership was divided, pressured by its Polish and East German counterparts, seriously troubled by Romanian dissent and worried about domestic developments” writes Scottish historian Maud Bracke (2003)

|

Going DeeperThe following links will help you widen your knowledge: Basic accounts from BBC Bitesize and from History.com Set of images from Radio Free Europe

YouTube The Prague Spring - clear narrative Journeyman TV - amazing footage; watch the first 5 minutes.

Podcast: |

CAUSESSummary:

|

|

In Detail:[i.e. Handbell Ringers of Great Britain]

1. A revolution of the Intelligentsia? American sociologist Jerome Karabel (1990) saw the Prague Spring in traditional Marxist terms as a conflict between the ‘reformist’ intellectuals and the ‘conservative’ apparatchiki (Communist officials) over the best future for socialism. There was a strong history of ideological opposition to hardline communism in Czechoslovakia.

There was thus general popular ideological pressure for reform.

2. Economic collapse and low living standards? The Communist takeover in 1948 had damaged the Czechoslovak economy:

The first sector in Czechoslovakia therefore to start reform was the ‘New Economic Model’ launched in 1965 by reformist Deputy Premier Ota Sik; it allowed cheaper imports, and encouraged private enterprise. It was a disaster because it encouraged people to ask for political reform.

3. Hostility to the Soviet Union? There was resentment of the Soviet Union. In the midst of the economic crisis, large amounts of goods were being sent to the Soviet Union without payment. Most of the uranium mined in Czechoslovakia went to the USSR, which steadily reduced the price it paid.

4. Repression? The Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia in 1948 had been followed by a fierce repression:

Many people alive in 1968 remembered that, between the wars, Czechoslovakia had been a democracy.

5. Government weakness? Although he was a hard-line communist, by 1968 President Novotny was discredited as a failure, and many politicians in the Czechoslovak Central Committee were writing to Brezhnev that he needed replacing. It needs to be pointed out that not everyone in Czechoslovakia wanted reform. Many Slovakian politicians – aware that the Slovak economy was weaker than the Czech economy – were opposed to the freeing up of competition. And there were powerful conservative voices who in April-May 1968 almost stopped the reform movement. All this made for a weak government which was unable to control the reform movement when it got started.

6. Brezhnev's Mistake? In December 1967, seeking his support, Novotny invited Brezhnev to Prague. Instead, Brezhnev supported his removal, leaving it to the Czechoslovaks to choose his successor. On 5 January 1968 they chose Alexander Dubcek … a decision Brezhnev later regretted.

|

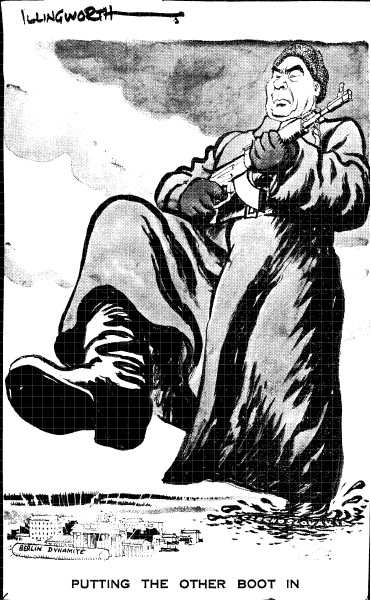

Source A

This British cartoon (1969) shows Brezhnev as a Russian solider.

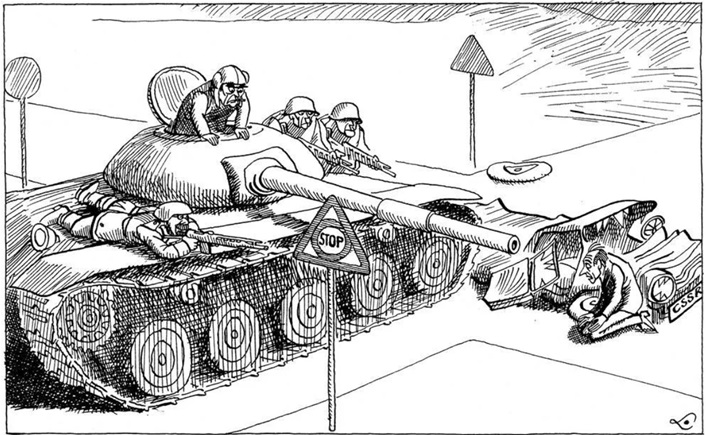

Source B

This West German cartoon (1

September 1968) is entitled 'Right of Way'.

Consider:1. Study and explain Sources A & B. In what ways are their messages similar, and in what ways different? 2. Given your understanding of the events of 1968 in Czechoslovakia, which do you think presents the more accurate portrayal? 3. Design a cartoon such as a Soviet cartoonist might have portrayed the invasion of Czechoslovakia.

|

EVENTSSummary:

|

Did You Know?Hungary also introduced some reforms in 1968, but its leader, Janos Kadar, went much slower, and tried to persuade Dubcek to do likewise. There is a story that, at one meeting in Moscow, Kadar said to Dubcek: "Don’t you realise the kind of people you are dealing with?"

|

In Detail:1. In April 1968, Dubcek announced an Action Programme of reform He called it ‘socialism with a human face’. The reforms included:

and he also promised:

2. The Czechs liked Dubcek’s reforms In Prague (the capital city of Czechoslovakia) people talked openly about politics for the first time in years. Films, songs and books were written which have become classics. “There was no other time in Czechoslovakian history that would be richer in cultural production of any kind” (Natalie Babjukova, 2015). Many young Czechs copied the ‘hippies’ of the West, played their guitars in the streets, and sang about love and peace; this time was called ‘the Prague Spring’.

3. Events in Czechoslovakia alarmed Soviet leaders As early as March 1968, comminst leaders and the KGB were complaining to Brezhnev that events in Czechoslovakia risked unsettling people in other communist countries. On 6 May Brezhnev declared it could cause “the complete collapse of the Warsaw Pact." On 17 June Ludvík Vaculík's Two Thousand Words was published, criticising the Czech Communist Party and calling for democracy and reform. On 3 August 1968, therefore, at a meeting of the Warsaw Pact, the USSR, East Germany, Hungary and Bulgaria signed the Bratislava Declaration, in which Czechoslovakia:

Brezhnev agreed to the reforms; he withdrew Soviet troops from Czechoslovakia.

4. On 13 August, Brezhnev phoned Dubcek He expressed his "alarm" that the Czechoslovak press was still attacking Communism and the Soviet Union (see Source C); what was Dubcek doing to “restore order in the mass media”? He wanted the matter resolving before the end of August. Dubcek could only tell him that it was a ‘complex situation’ and that he intended to hold a meeting of the Central Committee, perhaps in October, to discuss it.

5. On 18 August the Soviet government decided on the invasion of Czechoslovakia

6. On the night of 20-21 August 1968, 500,000 Warsaw Pact troops and 200 tanks invaded Czechoslovakia

|

Source CBREZHNEV: I must candidly say to you, Sasha, that by dragging your feet in the fulfillment of these obligations, you're committing outright deceit and are blatantly sabotaging the decisions we jointly reached. This posture toward the obligations you undertook is creating a new situation and is prompting us to reevaluate your statement. For this same reason we are considering new, independent decisions that would defend both the CPCz [the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia] and the cause of socialism in Czechoslovakia. Statement by Brezhnev during Dubcek's "disastrous" telephone conversation with him on 13 August. It is worth reading the whole conversation here.

Source DA judicious survey of the Czechoslovak reform movement shows its main weakness: the [failings] of its Marxist proponents in one of the Soviet bloc’s most Stalinist countries, highlighted by the blundering of the movement’s pathetic hero, Alexander Dubcek ... The Czechoslovak leaders were neither willing nor able to reassure the Soviet Union that they had things under control. Review by American historian Vojtech Mastny of a collection of essays on the Prague Spring (2012)

Consider:1. Close-read this page to find all the possible clues/ reasons you can as to why the 1968 Reform Movement failed. 2. Read Source C. Is it possible that Dubcek was unaware he was being given a last chance before the USSR intervened? 3. In the light of your answer to Q2, do you agree wth Mastny that 'pathetic' Dubcek was a major reason the Reform Movement failed? 4. Looking at your list of reasons the 1968 Reform Movement failed, and taking a wider view, did it ever have any chance of success? 5. Czechoslovakia failed to break free of Soviet control, Albania and Romania succeeded. Why? |

RESULTS1. Few Czechoslovakians fought back. Dubcek ordered the Czechs not to resist; only 72 people were killed. They put up barricades in the streets and took down road signs to confuse the soldiers, but it was hopeless. Brave students stood in front of the tanks; some put flowers in the barrels of the soldiers’ rifles. A few students (e.g. Jan Palach) set fire to themselves and burned to death as a protest.

2. Dubcek was flown to Moscow in handcuffs (he was not executed, but demoted to a woodsman). Hard line communist Gustav Husak replaced Dubcek, and freedoms were suppressed.

3. Romania criticised the invasion, and Albania left the Warsaw Pact. Overall, however, the suppression of the Prague Spring confirmed the Soviet hold over Eastern Europe.

4. In November 1968, Brezhnev formulated the Brezhnev Doctrine, that socialist countries had the right to suppress counter-revolutionary forces in any other socialist country. (In 2003, the American historian Michael Ouimet argued that, until the 1980s, the Soviet Union defined "any political threat to socialism in Eastern Europe as a threat to its domestic security"). The Doctrine marked the end of the ‘thaw’. Long-term this damaged Communist solidarity, not strengthened it.

5. The invasion did not stop the moves towards cooperation between the Soviet Union and the West:

6. Was 1968 a ‘watershed year’ - did it mark the beginning of the end for Soviet hegemony? Recent studies have seen the 1968 Prague Spring in its wider perspective, as half-way between the Communist takeover in 1948 and the ‘Velvet Revolution’ of 1989:

7. Maud Bracke has written of the power of ‘mystification’ (i.e. the romanticising) of the Prague Spring in popular consciousness – it still resonates today.

|

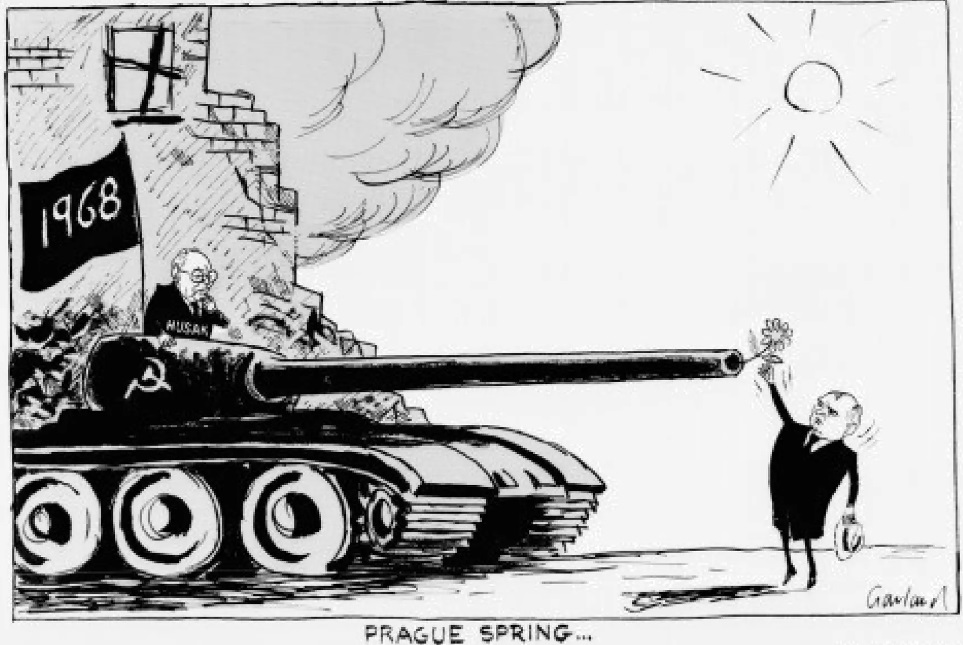

Source E

This British cartoon from

1987 is entitled ''Prague Spring'.

Consider:Gustav Husak was still President of Czechoslovakia in the late 1980s, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was introducing his policies of Glasnost and Perestroika. In 1987, after a furious debate in the Czechoslovak Politburo, Husak was forced to intoduce a series of reforms; two years later he fell from power. 1. Explain the meaning and the significance of the imagery in the cartoon.

|

|

| |