|

|

An Issue of FocusThis page first appeared on the web in June 2002, to help my pupils with a GCSE coursework essay. I have kept it as 'Part One' on this page because it interested and inspired them. The modern GCSE syllabus, however, requires you to consider ‘How far was the Somme a victory for the British army?’ ... which is a related issue, but requires a wider approach - so I have addressed that in 'Part Two'.

|

Before Action... I, that on my familiar hill The last poem of William Noel Hodgson (written just before the battle of the Somme). The son of a Bishop, Hodgson volunteered for the Devonshire

Regiment in Sept. 1914, at the age of 21. He was awarded the Military

Cross for his bravery on 25 Sept. 1915, when he and a small party held a

captured trench for 36 hours without food or reinforcements.

Consider:Read Part One of this web page. 1. Make a list of all the things (at least a dozen) you might claim to be ‘tragic’ – ie: examples of bad leadership/ examples of human suffering/ examples of failure. 2. ‘Generalise’ your points, to distinguish between the general point and the specific evidence. Draw up a two-column table, listing ‘Tragedies’ in one column, and ‘Evidence’ in the other. 3. Research the web links, especially the Somme documents, seeking further ideas why the Battle of the Somme might be regarded as a great military tragedy, and further evidence for all your ideas.

|

Going DeeperThe following links will help you widen your knowledge: Accounts: First Day of the Somme - map with accounts of engagements. Account of the first day, and a day-by-day diary of the rest of the battle BBC Animated map - helpful! The Somme after 1 July - an account by Peter Simkins Philip Gibbs account - the effect of the battle on the Germans

Pupils' essays:

Special Studies: Swavesey (inc map)

Source Documents

Film and Youtube Watch clips of the film Success or failure? - I'm Stuck

Powerpoints Mr Huggins' presentation on humour - ppt. |

Planning the BattleOn 1st July 1916, Haig and Joffre planned a joint attack on the German lines near Bapaume (although Haig would have preferred to fight further north). The action was designed to relieve some of the strain on the French at Verdun. Haig was quite hopeful that it would break through the German lines and bring the Allies victory. |

|

|

This 1916 cartoon from the Daily Mirror – entitled ‘The Somme Punch’ – shows the Somme as the Kaiser’s nose.

|

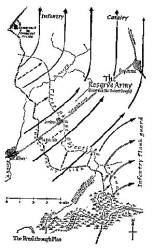

This map shows Haig’s plan – the army would break through the enemy lines, then the infantry and cavalry would sweep on past Bapaume.

|

Artillery BombardmentThe attack was preceded by an eight-day artillery bombardment, in which 1537 British guns fired 1,723,873 rounds. The sound of the bombardment could be heard in England. The aim of the bombardment was two-fold: firstly to kill the German soldiers and reduce them to shell-shocked chaos, secondly to destroy the German barbed wire. But the artillery failed. The shells were not powerful enough to break down into the German dug-outs (which were up to 9 metres deep), and the shrapnel shells, which consisted merely of cases filled with ball-bearings, did not destroy any of the wire, but simply made it more tangled and impassable.

|

The historian JM Bourne writes: ‘Rarely can so much effort have been expended to such little effect… Once the artillery failed, the infantry was doomed.’

|

1st JulyMines (tunnels) had been dug under the German trenches and packed with explosives. At 7.28 am these were detonated just before the British attack, giving the Germans 2 minutes warning. Then, at 7.30 am, whistles were blown and the men went ‘over the top’. Each man carried a gas mask, groundsheet, field dressings, trench spade, 150 rounds of ammunition and such extras as sandbags or a roll of barbed wire – up to 80 pounds of equipment. Thinking that the Germans had been destroyed by the bombardment, and fearing that their inexperienced soldiers would become disorganised in a rush attack, the generals had ordered that the men should walk, in straight lines, across No Man’s Land. They were slaughtered. ‘They went down in their hundreds. You didn’t have to aim, we just fired into them,’ wrote one German machine-gunner. One British battalion was unable to advance because it could not climb over the bodies of the dead and wounded blocking the way. The British officers, ordered to carry only a pistol, and leading their troops by example, were easily marked out and shot – the result was chaos. Even seasoned soldiers were shocked. At this point a British commander decided to detonate a mine which had failed to explode, burying his own men under a hail of rock and soil. Some British units captured enemy positions, but in the afternoon the Germans counter-attacked and recaptured most of the land they had lost.

|

Blackadder Goes Forth: Goodbyee gives a vivid impression of the slaughter involved in going ‘over the top’. The phrase is still used today to describe something excessively stupid.

|

CasualtiesBritish casualties on the first day were 20,000 dead and more than 35,000 wounded – ‘probably more than any army in any war on a single day’. The British soldiers at the Somme were not conscripts – they were volunteers, who had flocked to join up in response to Kitchener’s ‘Your country needs you’ poster. In the First World War, men from the same town served together in the same regiment; now they were killed together. Friends and brothers died side by side, and towns lost all their young men in the same battle. Despite the setback of the first day, Haig – in his HQ in the château at Valvion, 50 miles behind the lines – was still confident. He continued the attacks for 4 more months. He made a major attack, following the same plan, and with the same results, in September.

|

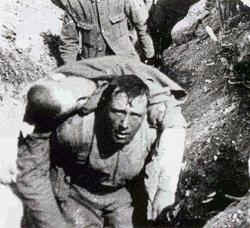

A wounded man is rushed to the Forward Dressing Post. Half an hour later, he was dead.

|

ConsequencesBy August, questions were beginning to be asked – Lloyd George lost confidence in Haig. At home, there was grief and horror. A propaganda film – designed to encourage support for the war by showing the public what the men were going through – was well-received by many people as a 'glimpse of what our soldiers are doing and daring and suffering in Picardy'(The Times). But not everyone welcomed it; one wounded soldier had to be led hysterical from the cinema, and one woman, after a stunned silence, shrieked out: ‘They’re dying!’ Nevertheless, the film was seen by 20 million people in Britain, as well as world-wide. At the front, also, morale began to fall. Soldiers were shot for ‘cowardice’, but bravery was pointless. The British troops reached the limit of their endurance. Only on 18 November, as winter set in, did the battle grind to a halt. Bapaume had not been captured. Only 6 miles of ground had been taken. Estimates of casualties vary widely: most historians put British casualties at about 420,000, French somewhere between 154,000 and 204,000, and Germans' anywhere from 270,000 (Winston Churchill) to 600,000 (the British official history, which had added 27% to the calculated figure for 'woundings'). 15 divisions of the 52 engaged in the battle lost their entire infantry strength. At the end of the battle, British and French forces had advanced 10 km at the cost of 42 British casualties per metre. Lloyd George called

the battle of the Somme: ‘The most gigantic, tenacious, grim, futile and

bloody fight ever waged in the history or war’.

|

Consider:Do the assignment: Why is the Battle of the Somme regarded as such a great military tragedy? Write the essay as a series of paragraphs, one point to each paragraph. For each point, give evidence of the tragedy. Don’t forget to explain why this was a tragedy, remembering to say how great a tragedy it was, and linking it to other points.

|

|

PART TWO - Was the Somme a Victory for the British Army?

Victory: 'the overcoming of

an enemy or antagonist; achievement of mastery or success in a struggle against

odds or difficulties’

The General'Good-morning; good-morning!' the General said

Siegfried Sassoon.

|

Source C

This poster shows a caricature of Haig, with the words: ‘Your Country Needs Me… like a hole in the head – which is what most of you are going to get’.

Source DWas Haig right to press on with the Battle of the Somme? As to whether it were wise or foolish to give battle on the Somme, there can surely be only one opinion. To have refused to fight then and there would have meant the abandonment of Verdun to its fate and the breakdown of co-operation with the French. From Duff Cooper's biography of Haig, officially authorised by Haig’s family (1936) Question: do you agree that Haig had no alternative but to fight on the Somme? And if he HAD to fight, did he HAVE to sacrifice so many men?

Source E

British soldiers with two German prisoners at the Somme. Does this picture prove Haig’s claim that ‘the German soldiers are now practically beaten men’?

Source F

Tanks were used for the first time at the battle of the Somme. However, they had serious problems, and did not bring the hoped-for breakthrough.

|

What did Haig think?Haig was unperturbed by the losses on the Somme, even though he lost the support of Lloyd George. He had the confidence of the king, and there was no-one to replace him. Even so, he felt the need to defend himself. In December he reported to the Cabinet what he claimed the battle had achieved: Source AThe Effects of the Battle of the Somme, according to General Haig The object of that offensive was threefold • To relieve the pressure on Verdun. • To assist our Allies in the other theatres of war by stopping any further transfer of German troops from the Western front. • To wear down the strength of the forces opposed to us... The three main objects with which we had commenced our offensive in July had already been achieved at the date when this account closes... Verdun had been relieved; the main German forces had been held on the Western front; and the enemy's strength had been very considerably worn down. Any one of these three results is in itself sufficient to justify the Somme battle. The attainment of all three of them affords ample compensation for the splendid efforts of our troops and for the sacrifices made by ourselves and our Allies. They have brought us a long step forward towards the final victory of the Allied cause. Part of a report written in December 1916, sent by Haig to the British Cabinet and published in the newspapers about the aftermath of the Battle of the Somme (ie this was his report to the people).

Source BThe Justification of the Battle of the Somme, according to General Haig A considerable portion of the German soldiers are now practically beaten men, ready to surrender if they could, thoroughly tired of the war and expecting nothing but defeat. It is true that the amount of ground we have gained is not great. That is nothing. We have proved our ability to force the enemy out of strong defensive positions and to defeat him. The German casualties have been greater than ours. Part of a report sent by Haig in 1916 to the Chief of Imperial General Staff (ie this was his report to the Army).

To a degree, Haig was correct. There is evidence that the Germans were disheartened by the Battle of the Somme:

So it can be argued that, although they did not give ground during the battle, the Germans from that moment on knew they could not win the war.

|

|

15 ideas to help you consider the question

|

A Personal CommentWhen I was your age, there was a (dark) joke about the assassination of the American President Lincoln: Apart from that, Mrs Lincoln, did you enjoy the opera? The (cruel) humour lay in ridiculousness of the disparity between what happened, and the comparative inconsequentiality of the question.

It strikes me that the Battle of the Somme is the same; the question: Apart from the 420,000 casualties, was the battle a success? would be similarly laughable, were it not so tragic.

Consider:Read Part Two of this webpage. 1. Read Source A and discuss: 'Does Haig’s assertion that the battle met his objectives make it a victory?' 2. Read Source B and discuss: 'What for Haig justified the lack of advance and does that make it a 'victory?' 3. Use the '15 ideas', Sources A-F, and your own knowledge to create a balance sheet of the overall success or failure for the British Army. What is the difference between a ‘victory’ and a ‘success’, and is it significant? 4. Do the assignment: How far was the Somme a victory for the British army? As well as a section listing and explaining the 'arguments it was a victory', and another section listing and explaining the 'arguments it was not a victory', you will need a final section where you weigh the two sides and come to a balanced conclusion.

|

|

| |