|

| |

Historiography of General Foch

Ferdinand Foch was a leading French military theorist before WWI (a Professor at the École Supérieure de Guerre), and a prominent General throughout the war, rising to Supreme Allied Commander in 1918. He played a significant role in the War, but historians have debated his strategic ability, leadership qualities and impact on the eventual Allied victory.

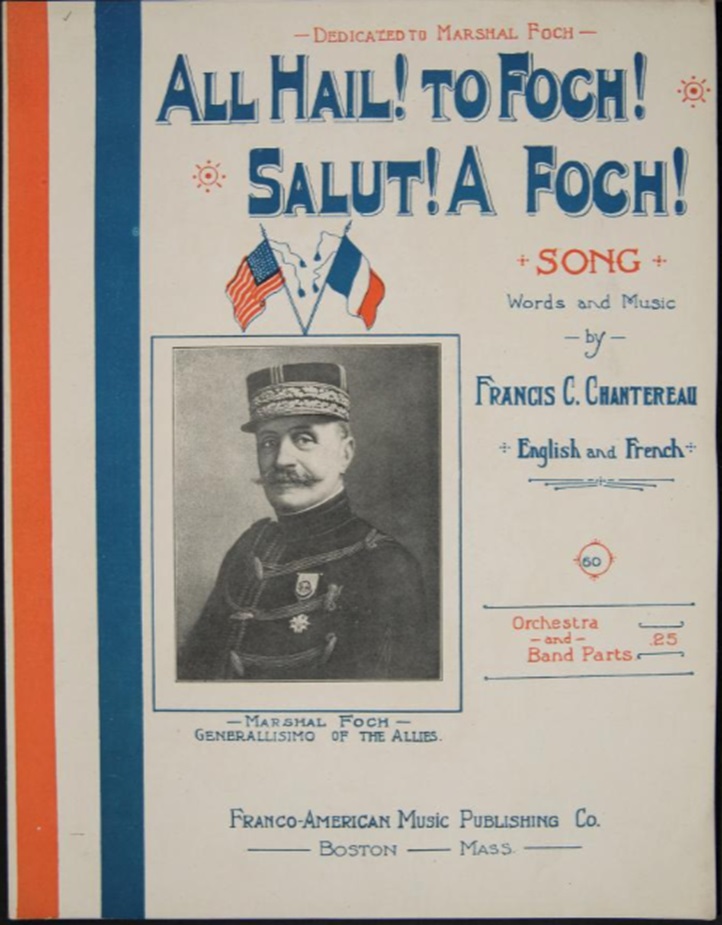

Hero of the Great WarIn 1920, a song came out in French and English : All Hail! To Foch! – which sums up much of the earliest works on Foch. The American biographer Clara E Laughlin (1918) wrote in a similar vein: “All hail to the military genius who reorganized our armies in the face of a flushed and triumphant foe, and striking with consummate skill, blow after blow, freed the world of its most dangerous exponents of autocracy and militarism, exploded the unholy fallacy that right is simply a synonym of might and brought to pass the dawning of a day of peace that has made the world safe for democracy!” For the French journalist Raymond Recouly (1920), he was “the winner of the war”: “a man who stands face to face with reality. No man can be a great leader unless there is balance between his intellect and character. In the case of Foch this balance is, humanly speaking, perfect.” Statues were erected in Paris and London. The American town of Indianapolis held a ‘Marshal Foch Day’ on 4 November 1921. Churchill (1937) felt that “the valour of his spirit and the shrewd sagacity of his judgment were of the highest order”. Even the French Prime Minister Clemenceau – who disliked Foch, thinking him too pro-Catholic and anti-Republican, and clashed with him publicly about the Treaty of Versailles after the war – wrote of Foch as a general (1930): “This frightful War brought us good generals, and many of those who have the right to risk an opinion will perhaps tell us that Foch was the most complete of them all … It was at Doullens that Foch, without anyone’s permission, laid hold of the command, and for that minute I shall remain grateful to him until my last breath.”

Revising Foch's reputationFoch’s reputation did not last long. As the excitement at victory gave way to reflection on the human cost of the fighting, historians became critical. The British military historian Basil Liddell Hart (1931) – in the book which became for decades the standard account of Foch in the English language – apologetically, and acknowledging that some of the blame lay on the limited technologies of the time, nevertheless shared that he had had to revise his assessment of Foch in his book, which: “brings out his too absorbing devotion to the offensive in the theory and practice of war – and the grave consequences not only to France but to her allies.“ During the 1960s and 1970s, things got worse. Foch’s theory of warfare – which was that attack wins wars, nor defence, but it must not be reckless attack – was distorted into mindless offensive à outrance, and he was lumped together with all the ‘châteaux’ generals, as unable to understand the changed nature of combat and sending thousands to a needless deaths in senseless offensives. The British historian AJP Taylor (1963) downplayed Foch’s importance as Generalissimo – he could give no orders, and the Allied commanders, who met only once, each more or less ploughed their own furrow: “Three separate armies fought to the end”. Even English military historian John Terraine, who argued that the Generals did as well as they could in the circumstances they faced, commented (1978): “Neither Foch’s tactics nor his strategy had ever been marked by subtlety; he was always a general who sought to impose his will on the enemy by relentless hammering.” Most of all, unlike Haig, who had retired after the war from everything except fundraising for the British Legion, Foch had gone into politics, and tried to obtain a tougher Treaty of Versailles, which earned him the criticism of American historian JC King (1960) as a soldier who interefered in politics, causing a crisis which almost overturned the Peace: “The usual term for this is insubordination”.

Post-1980s: a Growing AcknowledgementFrom the 1980s onward, historians began to acknowledge Foch's role the Allied victories of 1918 and also his willingness to learn from earlier failures. British historians began to realise that Britain did not win the war, but that France not only held most of the line, but lost most of the soldiers and provided most of the ordnance which won the war … and they were forced to acknowledge the contribution of French Generals such as Joffre, Pétain, Mangin … and above all Foch. Even then, this acknowledgement did not come without caveats, with Australian historians Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson writing in 1999 that Foch’s appointment to supreme command “did not have the military significance that some commentators have claimed.”

Only into the 21st century are we seeing robust defences of Foch. The Foch of American historian Michael Neiberg’s (2003) was responsible strategically, tactically, operationally and politically for the successes of 1918, and the book-jacket declares: “Better than any other general of the First World War, Foch came to understand how technology and modern alliance systems had changed the nature of warfare.” In 2009, British historian William Philpott noted that Foch deserved credit for the successful ‘Hundred Days’ offensive in 1918, and concluded: “Foch is perhaps the only First World War general who deserves recognition as one of the great captains of history.” Most of all, the late Elizabeth Greenhalgh (2011) strove to rehabilitate Foch both militarily and politically. The problem with many earlier writings about Foch, she argued, is that they were based upon the official war histories and biographies … no one had gone delving into the archives which, she found, revealed that: “Foch was not only an energetic ‘can-do’ commander, but also a thinker. His notebooks reveal a mind grappling with the problems of fighting a modern industrial war.”

|

|

|

| |