|

| |

|

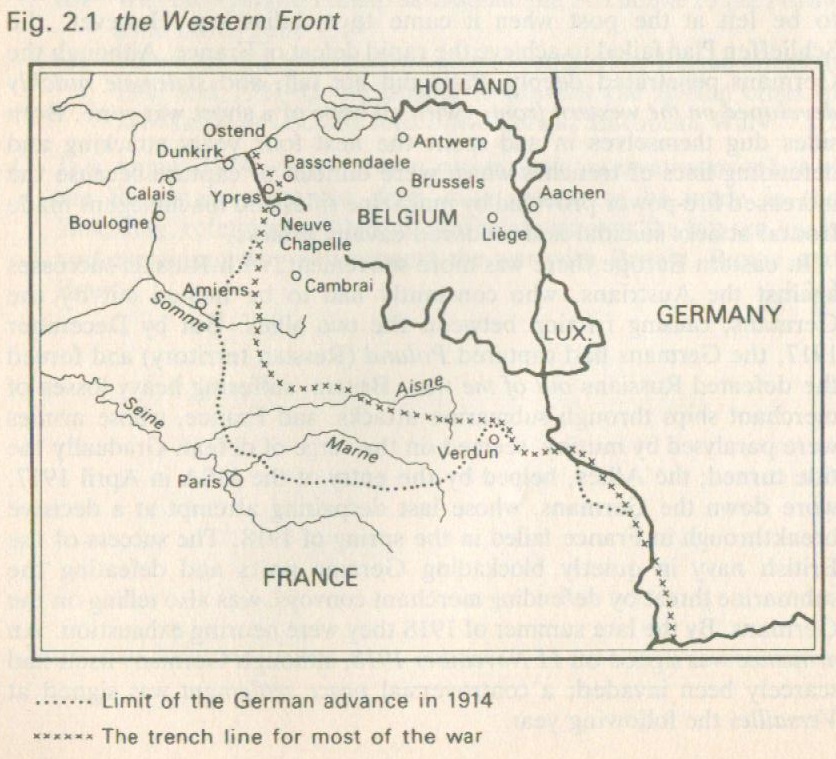

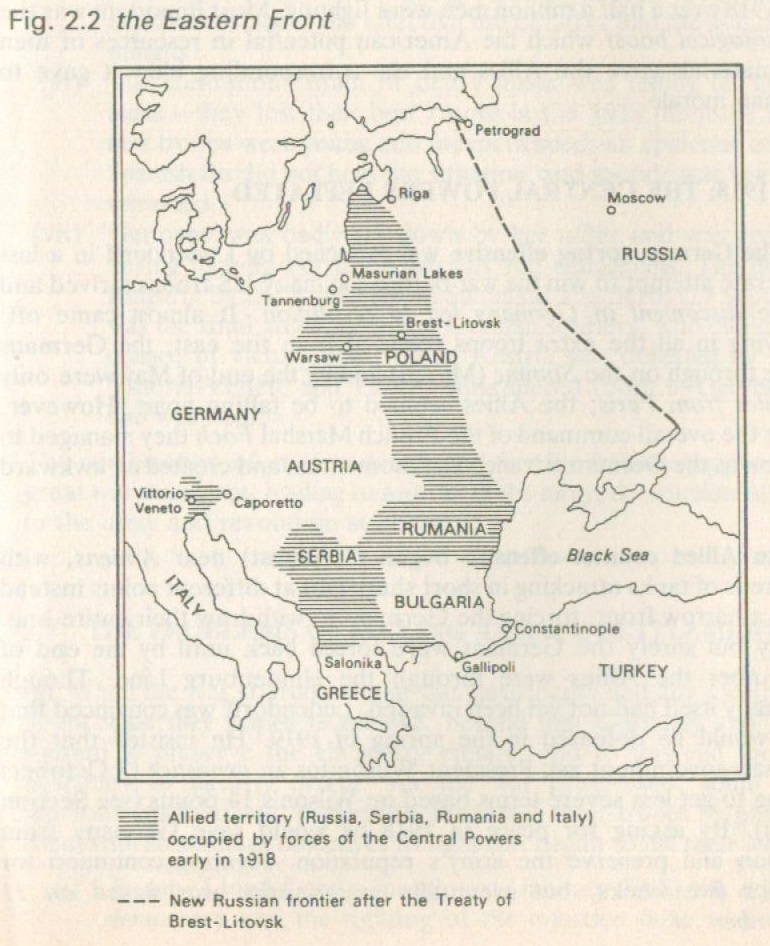

The two sides in the war were the Central Powers: Germany, AusŽtria-Hungary, Turkey (entered November 1914) and Bulgaria (October 1915); and the Allies: Russia (left December 1917). France. Britain, Italy (entered May 1915), Rumania (August 1916) and the USA (April 1917). The war turned out to be quite different from what most people had anticipated. It was widely expected to be a short decisive affair, like other recent European wars; hence Moltke's nervous determination not to be left at the post when it came to mobilisation. However. the Schlieffen Plan failed to achieve the rapid defeat of France. Although the Germans penetrated deeply, Paris did not fall, and stalemate quickly developed on the western front - with all hope of a short war gone. Both sides dug themselves in and spent the next four years attacking and defending lines of trenches which were difficult to capture because the increased fire-power provided by magazine rifles and machineguns made frontal attacks suicidal and rendered cavalry useless. In eastern Europe there was more movement, with Russian successes against the Austrians, who constantly had to be helped out by the Germans, causing friction between the two allies. But by December 1917, the Germans had captured Poland (Russian territory) and forced the defeated Russians out of the war. Britain, suffering heavy losses of merchant ships through submarine attacks, and France, whose armies were paralysed by mutiny, scented on the verge of defeat. Gradually the tide turned; the Allies, helped by the entry of the USA in April 1917, wore down the Germans, whose last despairing attempt at a decisive breakthrough in France failed in the spring of 1918. The success of the British navy in quietly blockading German ports and defeating the submarine threat by defending merchant convoys, was also telling on the Germans. By the late summer of 1918 they were nearing exhaustion. An armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, although Germany itself had scarcely been invaded; a controversial peace settlement was signed at Versailles the following year.

(a) On the western front the Schlieffen Plan was held up by unexpectedly strong Belgian resistance; it took the Germans over two weeks to capture Brussels, an important delay because it gave the French time to organise and left the channel ports free so that the British Expeditionary Force was able to land. Instead of sweeping round in a wide arc. capturing the Channel ports and approaching Paris from the west, the Germans found themselves making straight for Paris just east of the city. They penŽetrated to within twenty miles of Paris and the French government withdrew to Bordeaux; but the nearer they got to Paris, the more the German impetus slowed up; there were problems in keeping the armies supplied with food and ammunition and the troops became exhausted by the long marches in the August heat. In September the faltering Germans were attacked by the French under Joffre in the Battle of the Marne and driven back to the River Aisne, where they were able to dig trenches. This battle was vitally important; some historians even call it one of the most decisive battles of modern history. It ruined the Schlieffen Plan once and for all: France would not be knocked out in six weeks; hopes of a short war were dashed and the Germans would have to face full-scale war on two fronts. The war of movement was over; the trench lines eventually stretched from the Alps to the Channel coast, and there was time for the British navy to bring to bear its crippling blockade of German ports. The other important event of 1914 was that though the Germans took Antwerp, the British Expeditionary Force held grimly on to Ypres. which probably saved the other Channel ports so that more British troops could be landed and kept supplied. (b) On the eastern front the Russians, having mobilised more quickly than the Germans expected, made the mistake of invading both Austria and East Prussia at the same time. Though they were successful against Austria, occupying the province of Galicia, the Germans called HindenŽburg out of retirement and twice defeated the Russians at Tannenberg (August) and the Masurian Lakes (September), driving them out of Germany. These battles were important: the Russians lost vast amounts of equipment and ammunition which had taken years to amass. Although they had six and a quarter million men mobilised by the end of 1914, a third of them were without rifles. The Russians never recovered from this setback, whereas German self-confidence was boosted. When Turkey entered the war, the outlook for Russia was bleak, since Turkey could cut her main supply line through the Dardanelles. One bright spot for the Allies was that the Serbs drove out an Austrian invasion in fine style at the end of 1914, and Austrian morale was at rock bottom.

(a) In the west, the stalemate continued, though several attempts were made to break the trench line. The British tried at Neuve Chapelle and Loos, the French in Champagne while the Germans attacked again at Ypres. These, like all attacks on the western front until 1918, failed; always the difficulties were the same: there was no chance of a surprise attack because a massive artillery bombardment always preceded the infantry attack to clear the barbed wire from no man's land between the two lots of trenches, and generally to soften up the enemy; reconŽnaissance aircraft and observation balloons could spot troop concentraŽtions on the roads leading up to the trenches. Even when the trench line was breached, advance was difficult because the ground had been churned up by the artillery barrage and there was deadly machinegun fire to contend with. Any ground won was difficult to defend since it usually formed a salient or bulge in the trench line, of which the flanks were vulnerable. At Ypres the Germans used poison gas but when the wind changed direction it was blown back towards their own lines and they suffered more casualties than the Allies, especially when the Allies released some gas of their own. (b) In the east, Russia's fortunes were mixed: they had further successes against Austria, but met defeat whenever they clashed with the GerŽmans, who captured Warsaw and the whole of Poland. The Turkish blockade of the Straits was beginning to hamper the Russians, who were already running short of arms and ammunition. It was partly to clear the Dardanelles and open up the vital supply line to Russia via the Black Sea that the Gallipoli Campaign was launched, This was an idea strongly pressed by Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty) to escape the deadlock in the west by eliminating the Turks, thought to be the weakest of the Central Powers because of their unstable government. Success against Turkey would enable help to be sent to Russia and might also bring Bulgaria, Greece and Rumania into the war on the Allied side; it would then be possible to attack Austria from the south. The campaign was a total failure; the first attempt in March, an Anglo-French naval attack through the Straits to capture Constantinople, failed because of mines. This ruined the surprise element, so that when the British attempted landings at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula, the Turks had strengthened their defences and no advance could be made (April). Further landings by Australian and New Zealand troops (Anzacs) in April and British in August were equally useless and positions could be held only with great difficulty. In December the entire force was withdrawn. The consequences were serious: besides being a blow to Allied morale, it turned out to be the last chance of relieving Russia via the Black Sea and probably decided Bulgaria to join the Central Powers. ranco-British force landed at Salonika in neutral Greece to try and re lie,. Serbia, but it was too late. When Bulgaria entered the war in 1, edsa. Serbia was quickly overrun by Bulgarians and Germans. The year 1915 therefore was not a good one for the Allies; even a British army sent to protect Anglo-Persian oil interests against a possible Turkish attack became bogged down in Mesopotamia as it approached Baghdad and was besieged by Turks at Kut-el-Amara from December 1915 until March 1916, when it was forced to surrender. (c) In May, Italy declared war on Austria, hoping to seize Austria's Italian-speaking provinces as well as territory along the eastern shore of the Adriatic. A secret treaty was signed in London in which the allies promised Italy Trentino, the south Tyrol, Istria. Trieste. part of DalmaŽtia. Adalia, some islands in the Aegean and a protectorate over Albania. The Allies hoped that by keeping thousands of Austrian troops occupied, the Italians would relieve pressure on the Russians. But the Italians made little headway and their efforts made no difference to the eventual Russian defeat.

(a) On the western front, 1916 is remembered for two terrible battles, Verdun and the Somme. (i) Verdun was an important French fortress against which the GerŽmans under Falkenhayn launched a massive attack in February; they hoped to draw all the best French troops to its defence. destroy them and then carry out a final offensive to win the war. But the French under Petaln defended stubbornly and the Germans had to abandon the attack in June. The French lost heavily (about 315,000 men) as the Germans intended. but so did the Germans with over 280,000 dead, and nothing to show for it. (ii) The Battle of the Somme was a series of attacks, mainly by the British, beginning on 1 July and lasting through to November. The aim was to relieve pressure on the French at Verdun, take over more of the trench line as the French army weakened, and keep the Germans fully committed so that they would be unable to risk sending reinforcements to the eastern front against Russia. At the end of it all the Allies had made only limited advances varying between a few hundred yards and seven miles along a thirty-mile front. The real importance of the battle was the blow to German morale, as they realised that Britain (where conscription was introduced for the first time in May) was a military power to be reckoned with. Losses on both sides, killed or wounded, were appalling (Germans 6500:10; British 418,000; French 194.(100) and Haig (British Commander-in-Chief) came under severe criticism for persisting with suicidal frontal attacks: Hindenburg himself admitted in his Memoirs that they could not have survived many more campaigns like Verdun and the Somme. The Somme also contributed to the fall of the British Prime Minister, Asquith, who resigned in December 1916. after mounting criticism. (b) David Lloyd George became Prime Minister, and his contribution to the Allied war effort and the defeat of the Central Powers was invaluable. His methods were dynamic and decisive; already as Minister of MuniŽtions since May 1915 he had improved the supply of shells and machine-guns, encouraged the development of new weapons (the Stokes light mortar and the tank) which Kitchener (Minister of War) had turned down, and taken control of mines, factories and railways so that the war effort could be properly centralised. As Prime Minister during 1917 he set up a small war cabinet so that quick decisions could be taken, brought shipping and agriculture under government control and introduced the Ministry of National Service to organise the mobilisation of men into the army. He also played an important part in the adoption of the convoy system (see Section 2.4(e)). (c) In the east, the Russians under Brusilov attacked the Austrians in June (in response to a plea from Britain and France for some action to divert German attention away from Verdun), managed to break the front and advanced 100 miles, taking 400,000 prisoners and large amounts of equipment. The Austrians were demoralised, but the strain was exhausting the Russians as well. The Rumanians invaded Austria (August) but the Germans swiftly came to the rescue, occupied the whole of Rumania and seized her wheat and oil supplies - not a happy end to 1916 for the Allies.

The general public in Germany and Britain expected a series of naval battles of the Trafalgar type between the rival Dreadnought fleets. But both sides were cautious and dared not risk any action which might result in the loss of their main fleets. The British Admiral Jellicoe was particularly cautious; as Churchill pointed out, he 'was the only man on either side who could have lost the war in an afternoon.' Nor were the Germans anxious for a confrontation because they had only 16 of the latest Dreadnoughts as against 27 British. (a) The Allies aimed to blockade the Central Powers, preventing goods entering or leaving, and slowly starving them out. At the same time trade routes had to be kept open between Britain, her empire and the rest of the world, so that the Allies themselves would not starve. A third function of the navy was to transport British troops to the continent and keep them supplied via the Channel ports. The British were successful in carrying out these aims: they went into action against German units sell anted abroad and at the Battle of the Falkland Islands destroyed one of the main German squadrons. By the end of 1914 nearly all German armed surface ships had been destroyed, apart from their main fleet (which did not venture out of the Heligoland Bight) and the squadron Blockading the Baltic to cut off supplies to Russia. In 1915 the navy was Involved in the Gallipoli Campaign (see Section 2.2(b)). (b) The Allied blockade caused problems: Britain was trying to prevent the Germans using the neutral Scandinavian and Dutch ports to break the blockade; this involved stopping and searching all neutral ships and confiscating any goods suspected of being intended for enemy hands. The USA objected strongly to this, being anxious to continue trading with both sides. (c) The Germans retaliated with mines and submarine attacks, which was their only alternative since their surface vessels were either destroyed or blockaded. At first, they respected neutral shipping and passenger liners, but it was soon clear that the German U-boat blockade was not effective, partly because of insufficient U-boats and partly because of problems of identification, as the British tried to fool the Germans by flying neutral flags and using passenger liners to transport arms and ammunition. In April 1915 the British liner Lusitania was sunk by a torpedo attack. (it has recently been proved that the Lusitania was armed and carrying vast quantities of arms and ammunition, as the Germans well knew; hence their claim that the sinking was not just an act of barbarism against defenceless civilians.) This had important consequences: out of the thousand dead, 118 were Americans. President Wilson therefore found that the USA would have to take sides to protect her trade; whereas the British blockade did not interfere with the safety of passengers and crews, German tactics certainly did. For the time being, however. American protests caused Bethmann to tone down the submarine campaign, rendering it even less effective. (d) The Battle of Jutland (31 May) was the main event of 1916, the only time the main battle-fleets emerged and engaged each other; the result was indecisive. The German Admiral von Scheer tried to lure part of the British fleet out from its base so that that section could be destroyed by the numerically superior Germans. However, more British ships came out than he had anticipated, and after the two fleets had shelled each other on and off for several hours, the Germans decided to retire to base firing torpedoes as they went. On balance. the Germans could claim that they had won the battle since they lost only 11 ships to Britain's 14, but the real importance of the battle lay in the fact that the Germans had failed to destroy British sea power: the German High Seas Fleet stayed in Kiel for the rest of the war leaving Britain's control of the surface complete. In desperation at the food shortages caused by the British blockade, they embarked, with fatal results, on 'unrestricted' submarine warfare. (e) 'Unrestricted' submarine warfare (January 1917). As they had been concentrating on the production of U-boats since the Battle of Jutland, this campaign was extremely effective. They attempted to sink all enemy and neutral merchant ships in the Atlantic and although they knew that this was bound to bring the USA into the war, they hoped that Britain and France would be starved into surrender before the Americans could make any vital contribution. They almost did it: the peak of German success came in April 1917. when 430 ships were lost; Britain was down to about six weeks' corn supply and although the USA came into the war in April, it was hound to be several months before their help became effective. However, the situation was saved by Lloyd George who insisted that the Admiralty adopt the convoy system in which a large number of merchant ships sailed together protected by escorting warŽships. This drastically reduced losses and the German gamble had failed. The submarine campaign was extremely important because it brought the USA into the war. The British navy therefore, helped by the Americans, played a vitally important role in the defeat of the Central Powers, and by the middle of 1918 had achieved its three aims.

(a) In the west, 1917 was a year of Allied failure. A massive French attack under Nivelle in Champagne achieved nothing except mutiny in the French army, which was successfully sorted out by Main. From June to November the British fought the Third Battle of Ypres, usually remembered as Passchendaele, in appallingly muddy conditions; British casualties were enormous - 324,00) compared with 200,000 Germans for a four-mile advance. More significant was the Battle of Cambrai, which demonstrated that tanks, properly used, might break the deadlock of trench warfare. 381 massed British tanks made a great breach in the German line, but lack of reserves prevented the success from being followed up. However, the lesson had been observed and Cambrai became the model for the successful attacks of 1918. Meanwhile the Italians were heavily defeated by Germans and Austrians at Caporetto (October) and retreated in disorder. This rather unexpectedly proved to he an important turning point. Italian morale revived, perhaps because they were faced with having to defend their homeland against the hated Austrians. The defeat also led to the setting up of an Allied Supreme War Council. The new French premier Clemenceau, a great war leader in the Lloyd George mould, rallied the wilting French. (b) On the eastern front, disaster struck the Allies when Russia withdrew from the war. Continuous defeat by the Germans, lack of arms and supplies and utterly incompetent leadership caused two revolutions (see Section 3.2) and the Bolsheviks, who took over in November, were willing to make peace. Thus in 1918 the entire weight of German forces could be thrown against the west; without the USA the Allies would have been hard pressed. Encouragement was provided by the British capture of Baghdad and Jerusalem from the Turks, giving them control of vast oil supplies.

(c) The entry of the USA (April) was caused partly by the German U-boat campaign, and also by the discovery that Germany was trying to persuade Mexico to declare war on the USA, promising her Texas, New Mexico and Arizona in return. The Americans had hesitated about siding with the autocratic Russian government, but the overthrow of the tsar in the March revolution removed this obstacle. The USA made an importŽant contribution to the Allied victory: they supplied Britain and France with food, merchant ships and credit; actual military help came slowly. By the end of 1917 only one American division had been in action, but by mid-1918 over a half a million men were fighting. Most important was the psychological boost which the American potential in resources of men and materials gave the Allies and the corresponding blow it gave to German morale.

2.6 1918: THE CENTRAL POWERS DEFEATED (a) The German spring offensive was launched by Ludendorff in a last desperate attempt to win the war before too many US troops arrived and before discontent in Germany led to revolution. It almost came off: throwing in all the extra troops released from the east, the Germans broke through on the Somme (March) and by the end of May were only 40 miles from Paris; the Allies seemed to be falling apart. However, under the overall command of the French Marshal Foch they managed to hold on as the German advance lost momentum and created an awkward bulge. (b) An Allied counter-offensive began (8 August) near Amiens, with hundreds of tanks attacking in short sharp jabs at different points instead of on a narrow front, forcing the Germans to withdraw their entire line. Slowly but surely the Germans were forced back until by the end of September the Allies were through the Hindenburg Line. Though Germany itself had not yet been invaded. Ludendorff was convinced that they would he defeated in the spring of 1919. He insisted that the German government ask President Wilson for an armistice (3 October) hoping to get less severe terms based on Wilson's 14 points (see Section 2.7(a)). By asking for peace in 1918 he would save Germany from invasion and preserve the army's reputation. Fighting continued for another five weeks, but eventually an armistice was signed on 11 November. (c) Why did the Central Powers lose the war? The reasons can be briefly summarised: (i) Once the Schlieffen Plan had failed. removing all hope of a quick German victory, it was bound to be a strain for them, facing war on two fronts. (ii) Allied sea power was decisive, enforcing the deadly blockade which caused desperate food shortages, while keeping Allied armies fully supplied. (iii) The German submarine campaign failed in the face of convoys protected by British, American and Japanese destroyers; the campaign itself was a mistake because it brought the USA into the war. (iv) The entry of the USA brought vast resources to the Allies. (v) Allied political leaders at the critical time - Lloyd George and Clemenceau - were probably more competent than those of the Central Powers; the unity of command under Foch in 1918 probably helped, while Haig learned lessons from the 1917 experiences about the effective use of tanks and the avoidance of salients. (vi) The continuous strain of heavy lasses was telling on the GerŽmans - they lost their best troops in the 1918 offensive and the new troops were young and inexperienced; an epidemic of deadly Spanish flu did not help the situation, and morale was low as they retreated. (vii) Germany was badly let down by her allies and was constantly having to help out the Austrians and Bulgarians. The defeat of Bulgaria by the British (from Salonika) and Serbs (29 September) was the final straw for many German soldiers, who could see no chance of victory now. When Austria was defeated by Italy at Vittoria-Veneto and Turkey surrendered (both in October), the end was near. The combination of military defeat and dire food shortages produced a great war weariness, leading to mutiny in the navy, destruction of morale in the army and revolution at home. |

|

|

| |