|

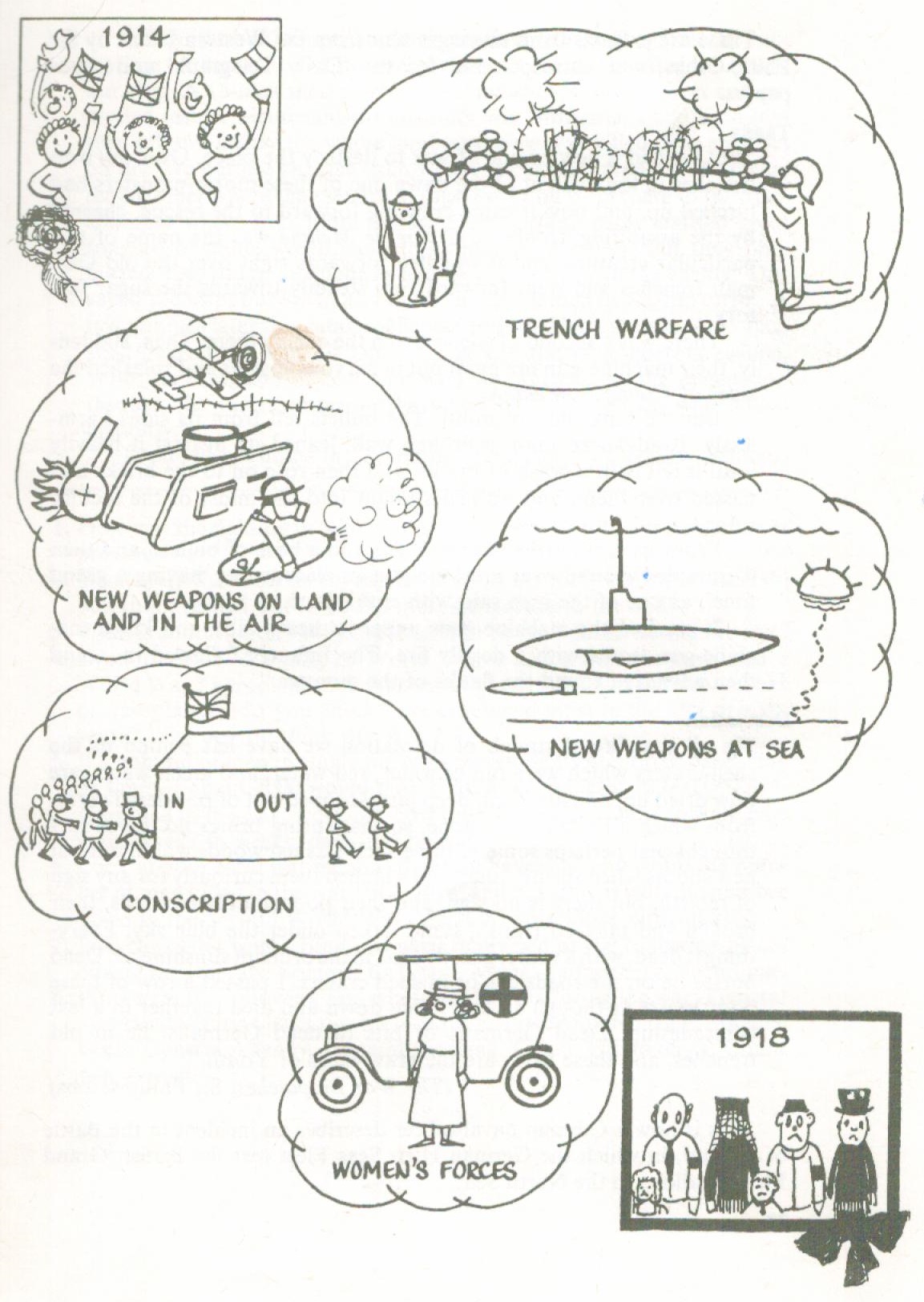

When war broke out in 1914 most of the people in Europe were pleased. War seemed rather exciting and glamorous, with gallant young men dash¬ing into battle—preferably on horseback, of course—waving swords and flags. Four years later these dreams had vanished and a bitterly disillusioned Europe, with ten million of its best men dead, realised the true cruelty of modern war. There was no glamour here—nothing but stark horror, mi¬sery and tragedy.

There had been no major war in Europe for a century, and great changes had taken place in fighting methods. Science, engineering and all the resources of the industry that had developed during the nineteenth century were thrown into the battle for quicker ways of killing more and more men, and of doing more and more damage. The latest inventions, the motor engine, aeroplanes and wireless, unreliable and crude in 1914, soon developed under war conditions into efficient fighting machines. As the struggle went on, motor vehicles, which in pre-war days had been rare except in cities, and which were little more than a novelty for the wealthy, gradually drove out the horse as transport, and developed lethal sidelines such as tanks and self-propelled guns. The flying machine, which in 1914 was still a mad toy for mad men, soon established itself as a fighting ma¬chine, growing faster and faster, more lethal and less liable to crash. It was soon found too, that wireless, which was scarcely out of its laboratory, could be handled and operated by ordinary men on the battlefield. This too, grew more efficient and more reliable as the war dragged on.

In the actual fighting, instead of great cavalry charges by cheering, shouting soldiers, the armies of 1914 dug trenches in the earth, protected them with sandbags and barbed wire, and filled them with men armed with rifles, machine guns and hand grenades. Fifty, a hundred or two hundred metres away, the enemy did the same, and the object was to wipe out the men in the opposing trench by any possible means, and to capture the ground they defended.

Day and night heavy guns, made in the great new engineering factories and powered by the scientists' latest explosives, a hundred times more de¬structive than the simple gunpowder of previous wars, hurled thousands of tons of shells towards the enemy to blow him to bits. Tanks, after 1916, crawled through the enemy's barbed wire to crush him or shoot him to death: poison gas was poured from one trench to another when the windwas in the right direction to blind and suffocate with appalling suffering: machines hurled out jets of roaring flame, and when all other methods failed, there was still the old-fashioned rifle and bayonet to spear him.

The land for far around the front line trenches became a dead world—apart from the miserable living men who crouched in the shelter of the earth ditches. Grass, trees, houses—everything disappeared into a chaos of wreckage and rotting human remains lying in a sea of mud in winter and a bed of dust in summer.

Month after month, year after year, men battled out the war under in-describable hardships of mud, water, filth and fear. For the loss of fifty thousand men they might move forward one week and gain a few hundred metres of churned-up, useless ground: a fortnight later, for the loss of even more men, they might lose it again. For the whole four years of the war, the battle lines on the Western Front (Northern France and Belgium) where most of the fighting was done, did not move more than a few kilometres.

At sea it was much the same story. There was one great battle in which the fleets of Britain and Germany met face to face in the manner of Trafalgar (the battle of Jutland), but all the while submarines prowled beneath the waves ready to torpedo any enemy ship, armed or unarmed. Mines were sprinkled throughout the sea lanes to destroy anything, enemy or neutral, warship, merchant ship, passenger liner or even hospital ships. In the air, the early aeroplanes twisted and turned to spot enemy troop movements so that the men on the ground could know when to attack and when to retreat. Later on, the planes took to fighting their own little war in the air, and towards the end of the fighting a few German airships and some heavy bombing aeroplanes managed to reach England. Al¬though their bombs were small and they did relatively little damage, they gave a terrifying foretaste of what might be to come.

The struggle was so grim, and the slaughter so great, that the British government could no longer rely on men volunteering to fight, and in 1916 conscription was introduced for the first time. Now every fit man, the willing and the unwilling, the brave and the cowardly, was forced to join one of the fighting forces unless he was in a vitally important job. And when the supply was still not enough, women 'soldiers' and 'sailors' were brought in to do such duties as driving, office work and cooking so that the men could be released for actual fighting.

So, when the last shot was fired on November llth, 1918, the whole of Europe was so revolted by the horrors of the four years of destruction that everyone determined that this, the Great War, should be the last of wars—the 'war to end all wars' as they called it. Peace for ever, they said, had been bought with those ten million lives and countless millions of pounds of damage. If only they could have seen that within twenty-one years another war was to break out which would take five times as many lives as 'their' war!

These are extracts from messages sent from the Western Front by Sir Philip Gibbs, war correspondent for the 'Daily Telegraph' and other papers.

Tanks

"But we had a new engine of war to destroy the place. Over our own trenches in the twilight of the dawn one of these motor-monsters had lurched up, and now it came crawling forward to the rescue, cheered by the assaulting troops ... Creme de Menthe was the name of this particular creature, and it waddled forwards right over the old Ger¬man trenches and went forward very steadily towards the sugar fac¬tory.

There was a second of silence from the enemy there. Then, sudden¬ly, their machine-gun fire burst out in nervous spasms and splashed the sides of Creme de Menthe.

But the tank did not mind. The bullets fell from its sides harm-lessly. It advanced upon a broken wall, leaned up against it heavily until it fell with a crash of bricks, and then rose on to the bricks and passed over them, and walked straight into the midst of the factory ruins.

From its sides came flashes of fire and a hose of bullets, and then it trampled around over machine-gun emplacements, 'having a grand time', as one of the men said with enthusiasm.

It crushed the machine-guns under its heavy ribs, and killed ma-chine-gun teams with a deadly fire. The Infantry followed in ... and then advanced round the flanks of the monster."

Desolation

"In all that broad stretch of desolation we have left behind us the shell-craters which were full of water, red water, and green water, are now dried up, and are hard, deep pits, scooped out of powdered earth, from which all vitality has gone, so that spring brings no life to it. I thought that perhaps some of these shell-slashed woods would put out new shoots when spring came, and watched them curiously for any sign of rebirth, but there is no sign, and their poor, mutilated limbs, their broken and tattered trunks, stand naked under the blue sky. Every¬thing is dead, with a white, ghastly look in the brilliant sunshine, ... Dead horses lie on the roadsides or in shell-craters. I passed a row of these poor beasts as though all had fallen down and died together in a last comradeship. Dead Germans or bits of dead Germans, lie in old trenches, and these fields are the graveyards of Youth."

(The War Despatches, Sir Philip Gibbs)

This is how a German naval officer describes an incident in the Battle of Jutland, in which the German High Seas Fleet met the British Grand Fleet headlong in the North Sea:

"They (the battleships) hurled themselves recklessly against the ene¬my line. A dense hail of fire swept them all away. Hit after hit struck our ship. A 15-inch shell pierced the armour of 'Caesar' turret and ex¬ploded inside. Lieutenant-Commander von Boltenstern had both legs torn off and nearly the whole gunhouse crew was killed. The shell set on fire two cordite charges from which the flames spread to the trans¬fer chamber where they set fire to four more and from there to the case-chamber where four more ignited. The burning cases emitted great tongues of flame which shot up as high as a house; but they only blazed, they did not explode as had been the case with the enemy. This saved the ship, but killed all but five of the 70 men inside the turret. A few minutes later this catastrophe was followed by a second. A 15-inch shell pierced the roof of 'Dora' turret and the same horrors ensued. With the exception of one man who was thrown by the concussion through the turret entrance, the whole crew of 80 men were killed instantly."

(Von Hase, quoted in The Battle of Jutland, by Geoffrey Bennett)

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. How was the fighting in World War 1 completely different from that of previous wars?

2. What were the main new weapons used in the war? Which of these do you think turned out to be the most dangerous in the end?

3. What is conscription? Why did it have to be introduced during the war?

4. Draw pictures of a tank of World War 1 and a modern tank, and a World War 1 aeroplane and a modern fighter. Which of the two—tanks or aeroplanes—do you think have developed most in the fifty or sixty years? Why do you think this is so?

5. If a column of men in single file were marching by at a brisk pace—say 61 km/h— about 7000 would pass in an hour. At least 10,000,000 sol¬diers died in the war: work out how long these would take to walk past you (answer in weeks, days and hours).

|

|