|

Except

for a small number the children were filthy and in this

district we have never seen so many verminous children lacking

any knowledge of clean and hygienic habits.

from

an interview with a host family

verminous:

having lice and fleas.

|

Links

Snaith

Primary site - excellent &

easy

YouTube and other movies

BBC movie-animation

Film clips

Film clips

BBCi

Children of WWII site - simple

The

'HistoryLearning' site - basic

info

The

'BattleofBritain' on evacuations

The

BBCi site on evacuation (esp. the audio-memories)

- fab!

The

Bristol evacuees

The

govt's Learning Curve site

Evacuees'

memories (eye-opening)

Blackpool memories

Chesham at War: evacuation

Chesham at War: evacuation

An

extract from Norman Longmate's fantastic book: How We Lived

Then

|

|

The

government knew that cities would be bombed, and

thought that gas would be used. A million coffins were

prepared.

It was feared that many child casualties would

affect morale, so pressure was put on parents to send

the children away to the safety of the countryside.

Families

gathered at railway stations.

A label was tied to the children giving their

destination.

The evacuations began on 1st September 1939.

Some parents refused to allow their children to

leave, but amazing numbers sent them away.

Over one million evacuees left London by train.

School

children travelled with their teachers.

Children under five went with their mothers.

Pregnant women were also evacuated

For many children the journey was exciting,

they had never seen the country before. It was the

first time they had seen farm animals.

For many others it was the first time they had

been away from home and they were very distressed.

|

Source A

Government propaganda put immense pressure on

parents to send their children to the ‘safety’ of

the countryside.

In this poster, who is the ghostly figure

whispering ‘Take them back’?

Source

B

Evacuees on a

train out of London, September 1939.

All photographs like this were vetted by the

government before they were released.

|

Source

C

A

teacher remembers being evacuated

with children from her school

All

you could hear was the feet of the children and a kind of

murmur, because the children were too afraid to talk.

Mothers weren't allowed with us, but they came

along behind.

When we got to the station the train was ready.

We hadn't the slightest idea where we were going and

we put the children on the train and the gates closed

behind us. The mothers pressed against the iron gates

calling, 'Good-bye darling'.

from an

interview in 1988 with a teacher.

|

|

Many

evacuees felt homesick.

Strangers chose them and took them to live in

their homes.

They went to the local school and had to make

new friends. Some

ended up with brutal or dirty carers. The country was different to city life.

Some never settled down in their new homes.

Others – such as the comedian Kenneth

Williams – were happier with their new families than

they had been at home.

Very young children sometimes forgot their real

parents.

|

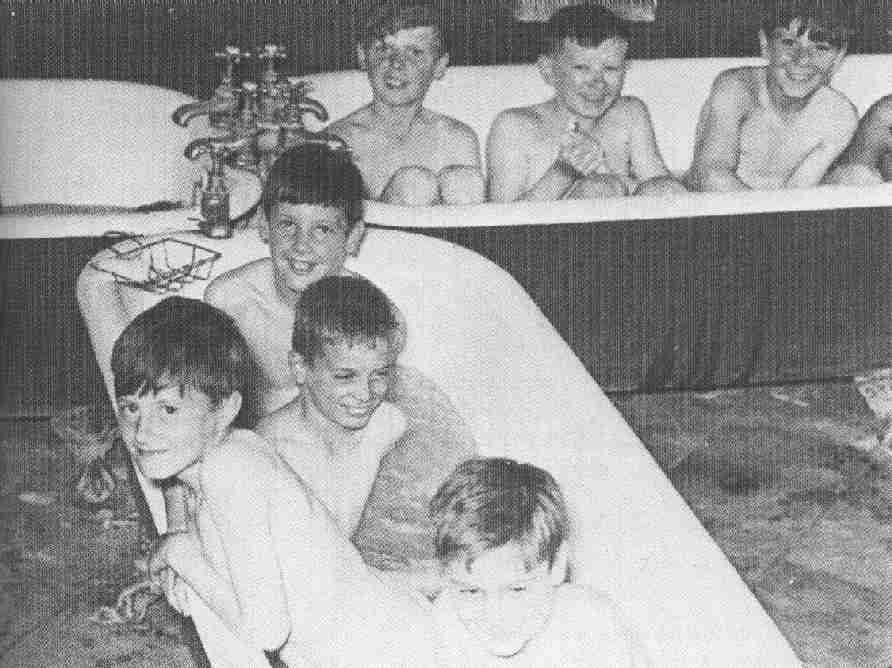

Source D

Evacuees

enjoying a bath – again, a photo published with government

permission.

This picture was published in London, where the

children’s mothers lived.

|

Country

people found the city children hard to cope with.

They were horrified by their ignorance – for

instance, many were amazed to find out that milk came

from a cow.

Many evacuees were poor – they had never worn

underclothes, eaten food from a table or slept in a

bed.

Some were filthy and naughty. Many wet the bed.

Source

E

The

mother of a host family looks back

The

children went round the house urinating on the

walls.

Although we had two toilets they never used

them.

Although we told the children and their

mother off about this filthy habit they took no

notice and our house stank to high heaven.

from

an interview in 1988 with the mother of a host

family

|

Source

F

An

evacuee looks back

How

I wish the common view of evacuees could be changed.

We were not all raised on a diet of fish and

chips eaten from newspaper, and many of us were

quite familiar with the origins of milk.

It is just as upsetting for a clean and

well-educated child to find itself in a grubby

semi-slum as the other way round.

from

an interview in 1988 with someone who was an evacuee

in 1939

|

Source

G

An

extract from a novel about evacuees

Miss

Evans looked down at their feet.

"Better change into your slippers before

I take you to your bedroom."

"We haven't any," Carrie said.

She meant to explain that there hadn't been

room in their cases for their slippers, but before

she could speak Miss Evans turned bright red and

said quickly, "Oh, I'm sorry, how silly of me,

why should you have slippers?

Never mind as long as you're careful and keep

to the middle of the stair carpet where it's covered

with a cloth."

Her brother Nick whispered, "She thinks

we're poor children, too poor to have

slippers," and they giggled.

Nina Bawden, Carne's War (1973)

A novel for children written by someone who had been an

evacuee.

|

Did

You Know?

The

immediate reaction of families, faced with a wild,

filthy urchin, was to blame the parents.

In time, however, they realised that poverty,

rather than parenting, was to blame.

For many middle-class people, it was the first

time they had seen poverty at first hand. In this way, evacuation was one factor which led people to

demand a Welfare State after the war.

|

There

was no bombing between September and Christmas so many

parents took their children home again. Some children were evacuated again the next year and some

stayed in the country for the whole of the war.

Source H

Relations

between evacuees and host families

Many

children, parents and teachers were evacuated when war

was declared. The evacuees were received at reception

centres and then placed with local families.

Arrangements, however, did not always go

smoothly. Unfortunately many evacuees could not settle

in the countryside. The country people were shocked at

the obvious poverty and deprivation of the town

children, not to mention their bad manners.

There were reports of children 'fouling'

gardens, hair crawling with lice, and bed wetting.

D Taylor, Mastering Economic & Social History

(1988)

David Taylor is a modern historian.

|

Extra:

1. Is there any

difference between Source A and Source B?

2. Look

at sources B and C.

Were evacuees excited at the idea of going

away?

3. Which

is more useful to an historian, Source B or Source C?

4.

Sources

E and F are interviews with people involved in

evacuation.

Why are they so different?

5. Source

G is from a children’s novel.

Is it therefore useless to historians?

|

|

|